Metformin alternatives are on many patients' radar when they hear about side‑effects or when blood sugar stays high despite treatment. Below is a quick snapshot of what you’ll learn:

- How Metformin works and why it’s first‑line.

- Key drug classes that can replace or complement it.

- A side‑by‑side table of efficacy, weight impact, heart benefits and cost.

- Which option fits different health profiles.

- Red flags that tell you to call your doctor.

What makes Metformin the go‑to choice?

When treating type 2 diabetes, Metformin is a big‑picture drug that lowers blood glucose by reducing liver production of sugar and improving muscle sensitivity to insulin. Its brand name, Glucophage, means “glucose eater.” First approved in the 1950s, it’s cheap (often under $5 a month in generic form) and has a long safety record.

Key attributes:

- Oral tablets taken once or twice daily.

- Typical dose 500‑2000mg per day.

- Weight neutral or modest weight loss.

- Reduces risk of heart disease in several large trials.

- Main side‑effects: mild stomach upset, occasional vitaminB12 deficiency.

Because it hits three of the four pillars-cost, safety, efficacy-guidelines worldwide list Metformin as the first medication after lifestyle changes.

When doctors look beyond Metformin

Not every patient stays on Metformin forever. Kidney function, gastrointestinal intolerance, or insufficient glucose control can push clinicians toward other drug classes.

Here are the most common alternatives, each with a distinct mechanism.

Sulfonylureas (e.g., glipizide, glyburide) stimulate the pancreas to release more insulin. They are inexpensive but can cause low blood sugar (hypoglycemia) and weight gain.

DPP‑4 inhibitors (e.g., sitagliptin, saxagliptin) block an enzyme that destroys incretin hormones, extending insulin release after meals. They are weight‑neutral and have low hypoglycemia risk, but cost more than Metformin.

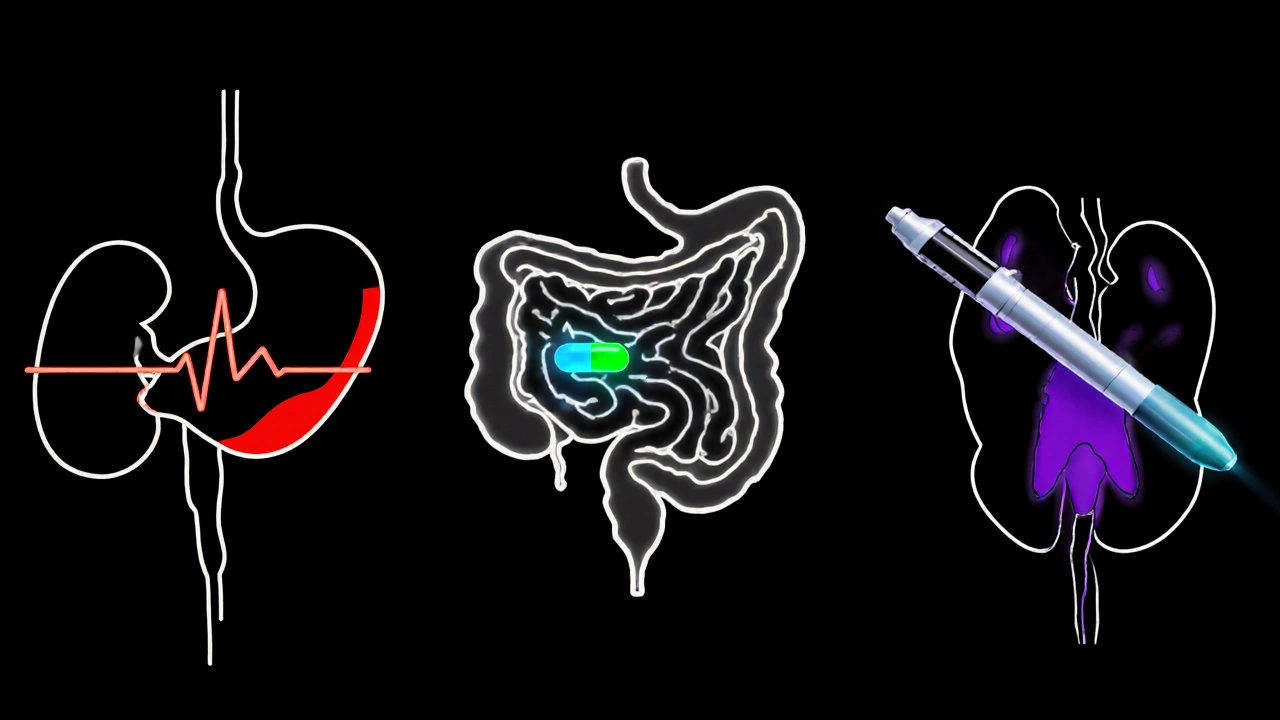

GLP‑1 agonists (e.g., liraglutide, semaglutide) are injectable (some weekly) peptides that mimic incretin, promoting insulin, suppressing appetite and often producing notable weight loss. They also lower cardiovascular events, yet injections and price can be barriers.

SGLT2 inhibitors (e.g., empagliflozin, canagliflozin) force the kidneys to dump excess glucose in urine. They cut weight, lower blood pressure, and have proven heart‑failure benefits, but can increase urinary infections.

Pioglitazone belongs to the thiazolidinedione family, improving insulin sensitivity in fat and muscle cells. It works well when Metformin alone isn’t enough, but may cause fluid retention and weight gain.

Insulin therapy is the final step for many patients. It provides the most reliable glucose control but requires injections, careful dose titration, and carries hypoglycemia risk.

Side‑by‑side comparison

| Drug class | Example | How it works | Typical dose | Weight effect | Heart/CKD benefit | Main side‑effects | Monthly cost (USD) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biguanide | Metformin (Glucophage) | Reduces liver glucose output, ↑ insulin sensitivity | 500‑2000mg | Neutral or ↓ | ↓ CV events, safe in early CKD | GI upset, B12 ↓ | $5‑$15 (generic) |

| Sulfonylurea | Glipizide | Stimulates pancreatic β‑cells | 5‑10mg | ↑ | None proven | Hypoglycemia, weight gain | $10‑$20 |

| DPP‑4 inhibitor | Sitagliptin | Blocks DPP‑4 → ↑ GLP‑1 | 100mg | Neutral | Neutral | Headache, nasopharyngitis | $40‑$60 |

| GLP‑1 agonist | Semaglutide (weekly) | Mimics GLP‑1 → ↑ insulin, ↓ appetite | 0.5‑2mg weekly | ↓ (5‑10kg) | ↓ MACE, ↓ kidney decline | Nausea, vomiting | $800‑$900 |

| SGLT2 inhibitor | Empagliflozin | Blocks glucose reabsorption in kidney | 10‑25mg | ↓ (2‑3kg) | ↓ heart‑failure, ↓ CKD progression | UTIs, genital yeast | $200‑$250 |

| Thiazolidinedione | Pioglitazone | Activates PPAR‑γ → ↑ insulin sensitivity | 15‑45mg | ↑ | Possible CV benefit | Fluid retention, bone loss | $30‑$40 |

| Insulin | Glargine (basal) | Replaces missing insulin | Variable, mg/kg | Neutral | Critical for type 1, advanced type 2 | Hypoglycemia, weight gain | $30‑$60 |

How to pick the right partner for your diabetes plan

Think of medication choice as matching a car to a driver. You need to consider mileage (glycemic control), terrain (kidney function), budget, and comfort with the controls (side‑effects, injection fear).

Key decision points:

- Kidney health. If eGFR falls below 45ml/min, Metformin dose must be reduced and SGLT2 inhibitors get a dose cut‑off, while some sulfonylureas become unsafe.

- Weight goals. Patients wanting weight loss often gravitate to GLP‑1 agonists or SGLT2 inhibitors; those indifferent may stay with Metformin or sulfonylureas.

- Cardiovascular risk. Empagliflozin and semaglutide have the strongest heart‑failure data, making them attractive for patients with prior CV events.

- Cost tolerance. Insurance coverage varies. Metformin remains the cheapest; many plans cover generic DPP‑4 inhibitors but not the newest GLP‑1 agents.

- Side‑effect tolerance. If nausea is a deal‑breaker, avoid GLP‑1. If urinary infections are a concern, think twice about SGLT2.

Often the best regimen mixes Metformin with another class. For example, Metformin + a DPP‑4 inhibitor gives solid glucose control without much hypoglycemia risk, while Metformin + an SGLT2 inhibitor adds weight loss and kidney protection.

Real‑world scenarios

CaseA: 55‑year‑old teacher, BMI31, eGFR70. He started Metformin but still has A1C8.2%. Adding a GLP‑1 agonist dropped A1C to 6.9% and shed 12lb. The weekly injection was acceptable because the cost was covered by his employer’s health plan.

CaseB: 68‑year‑old retiree, chronic kidney disease stage3 (eGFR38), concerned about pills. Metformin dose was halved, and an SGLT2 inhibitor was added. Within three months her A1C fell to 7.0% and blood pressure improved, with no urinary infections.

CaseC: 45‑year‑old entrepreneur, low income, no insurance. He could not afford brand‑name drugs. A combination of generic Metformin and a sulfonylurea kept his A1C at 7.5% for two years, though he experiences occasional mild hypoglycemia after missed meals.

These snapshots show that the “best” alternative depends on personal health numbers, finances, and preferences.

Practical tips for switching or adding a drug

- Start any new oral agent at the lowest dose and titrate every 1-2weeks.

- When adding a GLP‑1 agonist, begin with a “starter” dose to limit nausea.

- Check vitaminB12 levels after six months on Metformin.

- Monitor eGFR every three months if you’re on Metformin + SGLT2.

- Keep a simple log: fasting glucose, any symptoms, and medication changes.

Always discuss changes with your health‑care provider, especially if you take other medicines such as blood thinners or blood pressure pills.

When to seek professional help

If you notice any of these red flags, call your doctor promptly:

- Persistent nausea or vomiting that leads to dehydration.

- Signs of low blood sugar: shakiness, sweating, confusion.

- New urinary pain, fungal infections, or foul‑smelling urine.

- Swelling of ankles, sudden weight gain, or shortness of breath.

- Unexplained fatigue after starting Metformin, which could hint at B12 deficiency.

Early intervention can prevent complications and keep you on track toward target A1C levels.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I stop Metformin if I start a GLP‑1 agonist?

Many doctors taper Metformin gradually rather than stopping cold‑turkey, especially if kidney function is still good. Keeping a low dose can preserve its liver‑glucose benefits while you enjoy the weight loss from the GLP‑1.

Why does Metformin sometimes cause a vitamin B12 drop?

Metformin interferes with the intestinal absorption of B12. Testing every 1‑2years and supplementing if needed prevents anemia and nerve issues.

Are SGLT2 inhibitors safe for people without heart disease?

Yes. Even without prior heart problems, SGLT2 inhibitors lower blood pressure and promote modest weight loss, which can be preventive. Just watch for urinary infections.

How does a sulfonylurea differ from Metformin in blood sugar control?

Sulfonylureas force the pancreas to release insulin regardless of glucose level, which can cause lows. Metformin works upstream by cutting the liver’s sugar output, so it rarely causes hypoglycemia.

What should I do if I gain weight on a thiazolidinedione?

Talk to your doctor about reducing the dose or switching to a class with weight‑loss benefits, such as an SGLT2 inhibitor or GLP‑1 agonist. Lifestyle changes can also offset the fluid‑retention effect.

Anshul Gandhi

October 15, 2025 AT 20:13Don't be fooled by the glossy pharma ads – they don't want you to know how much they profit from keeping you on cheap Metformin while pumping you full of experimental add‑ons. The industry rigs guidelines to push pricey GLP‑1s and SGLT2s straight into your pharmacy, even when your kidneys can handle Metformin fine. They hide the long‑term B12 depletion risk and claim it's "rare" while the data shows a steady rise in deficiency cases. Wake up and read the fine print before you hand over another paycheck to the drug companies.

Emily Wang

October 15, 2025 AT 21:03Take charge of your health journey – talk to your doctor about mixing Metformin with a low‑dose GLP‑1 if weight loss is your goal, and keep a log of your glucose numbers to see real progress!

Emma French

October 15, 2025 AT 21:53Overall, the table does a solid job of laying out efficacy versus cost, which helps patients match meds to their lifestyle.

Rohit Poroli

October 15, 2025 AT 23:00When evaluating Metformin versus its alternatives, it's essential to consider both pharmacodynamic mechanisms and patient-specific comorbidities. Metformin belongs to the biguanide class and primarily reduces hepatic gluconeogenesis while enhancing peripheral insulin sensitivity, a dual action that translates into modest weight neutrality and a favorable cardiovascular profile as demonstrated in the UKPDS. Sulfonylureas, on the other hand, act as insulin secretagogues by binding to the SUR1 subunit of the pancreatic β‑cell potassium channel, which can precipitate hypoglycemia and promote weight gain – a trade‑off that may be acceptable in low‑income settings due to their low cost. DPP‑4 inhibitors inhibit the dipeptidyl peptidase‑4 enzyme, thereby prolonging endogenous incretin activity; they are weight neutral and have a low hypoglycemia risk, yet their incremental A1C reduction is modest compared with GLP‑1 receptor agonists. GLP‑1 agonists such as semaglutide mimic the incretin hormone GLP‑1, augmenting glucose‑dependent insulin secretion, slowing gastric emptying, and suppressing appetite, which yields significant weight loss and cardiovascular benefit, albeit at a substantially higher price point and with injection-related adherence considerations. SGLT2 inhibitors reduce renal glucose reabsorption, leading to glucosuria, osmotic diuresis, modest weight loss, and proven reductions in heart failure hospitalization, but they also increase the risk of genital mycotic infections and require adequate renal function for efficacy. Thiazolidinediones activate PPAR‑γ, improving peripheral insulin sensitivity, but they are associated with fluid retention, weight gain, and potential bone loss, limiting their use in patients with heart failure risk. Lastly, basal insulin provides exogenous insulin to meet physiological needs, offering the most reliable glycemic control for advanced disease stages, yet it carries the highest risk of hypoglycemia and weight gain, and it imposes a considerable burden of dose titration. In practice, combination therapy often maximizes the complementary strengths of these agents – for example, Metformin plus an SGLT2 inhibitor leverages cost‑effective glucose lowering with cardiovascular protection, while Metformin plus a GLP‑1 agonist adds robust weight loss. Clinicians must also factor in renal function thresholds, cost‑access barriers, and patient preferences regarding oral versus injectable routes. Monitoring protocols should include periodic vitamin B12 assessments for Metformin users, eGFR checks when SGLT2 inhibitors are prescribed, and vigilant observation for signs of hypoglycemia with sulfonylureas or insulin. By aligning drug selection with individual health profiles, socioeconomic context, and risk tolerance, providers can optimize outcomes while minimizing adverse events.

William Goodwin

October 16, 2025 AT 00:06👏 Great summary, Rohit! 🌟 Combining Metformin with an SGLT2 can be a game‑changer for patients who need heart protection without breaking the bank. Remember, the best plan is the one you can stick to – keep the conversation open with your doc and adjust as life changes. 🚀

Dileep Jha

October 16, 2025 AT 01:13While the article paints a neat picture of drug classes, it conveniently ignores the emerging data on off‑label metformin use in oncology and anti‑aging. Those studies suggest that metformin's mitochondrial effects could be leveraged beyond glycemic control, a nuance the piece glosses over in favor of a commercial drug hierarchy.

Michael Dennis

October 16, 2025 AT 02:03The assertion that Metformin’s benefits extend to oncology lacks robust phase‑III evidence; most trials remain exploratory. A cautious interpretation would acknowledge the hypothesis without overstating clinical applicability.

Blair Robertshaw

October 16, 2025 AT 02:53this article is overhyped. metformin is cheap but its side effects r real, especially if u dont monitor b12.

Claus Rossler

October 16, 2025 AT 04:00One must question the very premise of juxtaposing pharmacoeconomics with patient autonomy as if they occupy the same epistemic plane. The narrative simplistically conflates efficacy with cost, thereby neglecting the nuanced ethical discourse surrounding equitable access to novel therapeutics. By reducing complex therapeutic decisions to a binary table, the author flattens the multidimensional reality of lived experience into a reductive algorithmic construct, which, while convenient, betrays a certain intellectual complacency.