Every year, millions of unused or expired pills, patches, and liquids end up in toilets and sinks. People do it because it seems easy-just flush and forget. But what happens when those drugs leave your bathroom? They don’t vanish. They enter rivers, lakes, and even drinking water. And they’re not just floating around harmlessly. Scientists have found antidepressants in fish brains, antibiotics in stream sediment, and hormones causing male fish to develop eggs. This isn’t science fiction. It’s happening right now, and it’s tied directly to how we dispose of medicine.

Why Flushing Medications Is a Problem

Most people don’t realize that wastewater treatment plants aren’t built to remove drugs. They’re designed to catch dirt, bacteria, and solids-not tiny chemical molecules like ibuprofen, metformin, or Xanax. When you flush a pill, it travels through pipes to a treatment facility, gets partially filtered, and then flows out into rivers or oceans. Studies show that over 80% of U.S. waterways contain traces of pharmaceuticals. In some cases, concentrations are high enough to affect aquatic life. For example, diclofenac, a common painkiller, has been linked to kidney failure in vultures in India. Estrogen from birth control pills has caused male fish to produce eggs-something called feminization. Antibiotics in waterways are helping bacteria evolve into superbugs that no longer respond to treatment. This isn’t just an issue for fish. These chemicals can move up the food chain. Plants absorb them. Small fish eat the plants. Bigger fish eat the small ones. Eventually, humans eat the fish. The levels are low, but the long-term effects are still unknown.What Happens When You Throw Medications in the Trash?

Some people think throwing pills in the garbage is safer than flushing them. It’s better, but not good enough. Medications in landfills can leak into groundwater through rainwater runoff. A study in Connecticut found acetaminophen concentrations in landfill leachate as high as 117,000 nanograms per liter-far above what’s found in treated wastewater. That’s because landfills aren’t sealed like tanks. They’re open pits with drainage systems that eventually connect to aquifers. Even if you seal pills in a plastic bag, they can still break down over time. Animals might dig them up. Children or pets could accidentally ingest them. And if the trash gets incinerated, some chemicals turn into airborne toxins. So while landfill disposal doesn’t directly pollute rivers, it creates other risks that are just as serious.The FDA’s ‘Flush List’-What’s Safe and What’s Not

The FDA once told people to flush certain drugs to prevent overdose or abuse. That list included powerful opioids like fentanyl patches and oxycodone tablets. The idea was simple: if someone steals your medicine cabinet, flushing these drugs reduces the chance of accidental poisoning or addiction. But here’s the catch: that list is tiny. As of October 2022, it only includes 15 medications-mostly high-risk opioids. Everything else? Don’t flush it. Most people don’t know this. A 2021 FDA survey found that nearly 60% of Americans still think flushing is acceptable for any expired pill. That’s a dangerous misunderstanding. The FDA never said flushing was environmentally safe. They said the risk of misuse outweighed the environmental risk-for those 15 drugs only. If you’re unsure whether your medication is on the list, check the label or ask your pharmacist. If it’s not on the list, don’t flush it. Period.

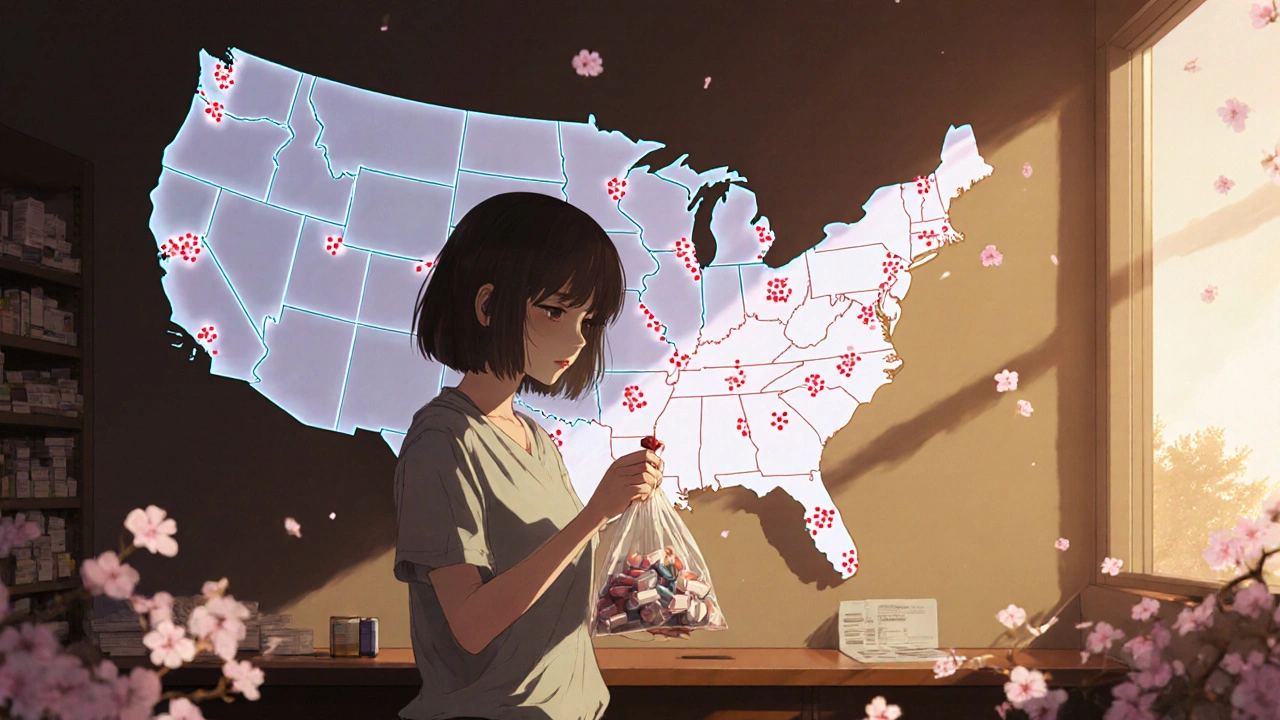

The Best Alternative: Take-Back Programs

The most effective way to dispose of unused medications is through take-back programs. These are drop-off locations at pharmacies, hospitals, or police stations where you can hand over old pills, creams, or inhalers for safe destruction. The drugs are collected, transported, and incinerated under strict environmental controls-no runoff, no leaks, no pollution. In the U.S., there are about 2,140 authorized collection sites nationwide. That sounds like a lot, but it’s not evenly spread. Rural areas often have none. In South Africa, where I live, take-back options are even scarcer. Many pharmacies don’t offer it. That’s why so many people end up flushing or tossing meds. But here’s the good news: you can still find options. Check with your local pharmacy. Call your city hall. Look for National Prescription Drug Take Back Day-hosted twice a year by the DEA. On those days, hundreds of sites open up across the country. Some communities have permanent drop boxes in police stations. If you’re lucky enough to live near one, use it. Even if you have to drive 20 minutes, it’s worth it.What If There’s No Take-Back Option?

If you live in an area with no take-back program and you can’t wait for a collection day, here’s what the EPA recommends:- Take the pills out of their original bottles.

- Mix them with something unappetizing-used coffee grounds, cat litter, or dirt.

- Put the mixture in a sealed plastic bag or container.

- Throw it in the trash.

Why Don’t More People Use Take-Back Programs?

The biggest reason? Lack of awareness. A 2023 survey found that only 30% of Americans know where to return unused medications. Many think expiration dates mean the drugs are dangerous to keep-so they flush them out of fear. Others hoard pills because they think they might need them again. One Reddit user wrote: “I kept my old antibiotics because I thought I’d use them if I got sick again. Turns out, I was poisoning the river without even knowing it.” Access is another barrier. In many towns, the nearest drop-off point is 30 miles away. Public transit doesn’t go there. People without cars just give up. And pharmacies? Most don’t promote take-back programs. They’re busy filling prescriptions. They don’t have staff to manage collection bins.

What’s Being Done to Fix This?

Europe is ahead of the curve. The European Union now requires drug manufacturers to pay for take-back programs. This is called Extended Producer Responsibility. If a company sells a pill, it’s responsible for how it’s disposed of. That’s changed the game. In countries like Germany and Sweden, over 70% of unused medications are returned to pharmacies. In the U.S., California passed a law in 2024 requiring pharmacies to give disposal instructions with every prescription. Other states are considering similar rules. Meanwhile, researchers are testing new wastewater filters that can remove up to 95% of pharmaceuticals-but these systems cost between $500,000 and $2 million per plant. Most cities can’t afford them. The real solution isn’t technology. It’s behavior. If people stopped flushing and started returning meds, we could cut environmental contamination from improper disposal by 60-75%, according to German environmental models.What You Can Do Today

You don’t need to wait for government action. Here’s what you can do right now:- Check your medicine cabinet. Go through expired or unused meds. Don’t wait for a “good time.”

- Call your local pharmacy. Ask if they have a take-back bin. If not, ask why.

- Find your nearest DEA take-back day. It happens in April and October. Mark your calendar.

- Don’t flush anything unless it’s on the FDA’s list. If you’re not sure, assume it’s not.

- Talk to your doctor. Ask for smaller prescriptions. Don’t get 90 pills if you only need 30.

Final Thought: It’s Not Just About Clean Water

This isn’t just about protecting fish or rivers. It’s about protecting ourselves. Every drug we flush or toss adds to a slow, invisible poison in our environment. We don’t know the full impact yet. But we know enough to act. The science is clear. The alternatives exist. What’s missing is action. You don’t need to be an activist to make a difference. Just stop flushing. Start asking questions. Use the drop-off bins. Help someone else understand why it matters. The water doesn’t care who you are. But it remembers what you flush.Is it ever okay to flush medications?

Yes, but only for specific high-risk medications listed by the FDA-currently only 15 drugs, mostly powerful opioids like fentanyl and oxycodone. These are the only exceptions. For every other pill, patch, liquid, or cream, flushing is harmful and should be avoided. Always check the label or ask your pharmacist before flushing anything.

What happens to medications after I drop them off at a take-back program?

Once collected, medications are transported to licensed facilities and incinerated at high temperatures under strict environmental controls. This process destroys the chemical structure of the drugs completely, leaving no residue to pollute water or soil. It’s the only disposal method that fully eliminates environmental risk.

Can I mix medications with water or alcohol before throwing them away?

No. Mixing medications with water or alcohol doesn’t destroy them-it just makes them more dangerous. Liquids can leak from trash bags and contaminate groundwater. Alcohol can make pills easier to extract and misuse. Always mix pills with something solid and unappetizing like coffee grounds, cat litter, or dirt. Seal it in a container. That’s the EPA’s recommended method.

Why can’t wastewater plants filter out drugs?

Wastewater plants are designed to remove solids, bacteria, and nutrients-not tiny, stable chemical molecules. Most pharmaceuticals are built to survive digestion and stay active in the body. That same stability makes them resistant to standard treatment. They pass through filters, settle in sludge, or flow out with treated water. Only advanced systems like ozone treatment or activated carbon can remove them-and they’re too expensive for most cities to install.

Are there any at-home devices that destroy medications safely?

Yes, but they’re not practical for most people. Products like Drug Buster use chemical powders to break down pills, but they cost around $30 per unit and require precise handling. They’re not widely available, and many don’t work on all drug types. For most households, the safest and cheapest option is still taking meds to a drop-off location or using the EPA’s trash method with coffee grounds or cat litter.

What should I do with empty pill bottles?

Remove or scratch out your personal information with a marker. Then recycle the bottle if your local program accepts #1 or #2 plastics. If not, throw it in the trash. Don’t reuse bottles for storing other items-especially around children. The plastic is safe to recycle, but the labels may contain sensitive data.

David vaughan

November 21, 2025 AT 03:19Wow. Just... wow. I had no idea flushing pills was this bad. I’ve been tossing them in the trash for years, thinking I was being responsible. Guess I was wrong. I’ll start mixing them with coffee grounds now. Thanks for the wake-up call. 🙏

Daisy L

November 21, 2025 AT 07:04Oh please. You’re acting like flushing one Advil is gonna sink the planet. We’ve got real problems-border crises, inflation, woke corporate nonsense-and you’re crying about fish getting high? Get a grip. This is liberal guilt theater dressed up as science.

Anne Nylander

November 23, 2025 AT 05:06YESSSS! I’m so glad someone finally said this!! 🙌 I just cleaned out my medicine cabinet last week and took everything to the pharmacy dropbox! It felt SO good!! You don’t need to be perfect, just start somewhere!! 💪✨

Noah Fitzsimmons

November 23, 2025 AT 14:08Oh, so now we’re supposed to believe that the EPA knows what’s best? Funny how they never mention that the same people who push ‘flush less’ are the ones who also want you to drink recycled toilet water. Wake up, sheep. This is all about control. They don’t care about fish-they care about your compliance.

Eliza Oakes

November 24, 2025 AT 14:18Wait-so you’re telling me I’m poisoning the environment because I flushed my Xanax after my dad died? That’s not a public health issue-that’s a trauma response. Now I’m supposed to feel guilty for grieving? Thanks, guilt-trip queen. 🙄

David Cusack

November 26, 2025 AT 06:12One must concede that the prevailing discourse on pharmaceutical disposal is, frankly, infantilizing. The notion that the average citizen can meaningfully impact aquatic biochemistry via coffee-ground mixing is not merely naïve-it is a grotesque misallocation of moral agency. The real issue lies in regulatory capture and the abdication of producer responsibility. The EU model, though imperfect, at least acknowledges that corporations-not consumers-must bear the burden. The American fixation on individual virtue signaling is not just ineffective; it is aesthetically offensive.

Michael Marrale

November 26, 2025 AT 07:48Did you know the government is putting microchips in the pills so they can track who flushes them? That’s why they’re pushing the take-back programs-so they can build a database of everyone who takes antidepressants. The fish? Just a distraction. The real goal is control. I checked the FDA list-fentanyl patches are on it, but not my blood pressure meds. Coincidence? I think not. 🕵️♂️

Corra Hathaway

November 27, 2025 AT 20:47Okay but-real talk-I just dropped off 12 bottles at the police station yesterday and cried because I felt so proud. 🥹 Like, I’m not a superhero, but I did something that matters. And guess what? My neighbor saw me and asked how to do it too. One person changes the vibe. You’re not alone. Let’s gooooooo!! 🌎💖

Clifford Temple

November 29, 2025 AT 09:43USA FIRST. If Europe wants to spend millions on fancy filters, let them. We’ve got real problems here-like illegal immigration and crumbling infrastructure. You think a fish dying from Xanax is worse than a kid getting shot in Chicago? This is why America’s losing. Stop crying about pills and start caring about your own country.